Some operational aspects of the OLT construction activity.

- Home, index, site details

- Australia 1901-1988

- New South Wales

- Overview of NSW

- Telegraph lines

- Telegraph Offices

- Date stamps

- Forms

- Envelopes

- Rates

- Stamps

- Queensland

- Overview of Qld

- Telegraph lines

- Telegraph offices

- Date stamps

- Forms

- Envelopes

- Rates

- Stamps

- South Australia

- Overview of SA

- Telegraph lines

- Telegraph Offices

- Date stamps

- Forms

- Envelopes

- Rates

- Stamps

- Tasmania

- Overview of Tasmania

- General developments

- Reports

- Organisation

- Telegraph lines

- Telegraph Offices

- Date stamps

- Railway lines

- Forms

- Envelopes

- Rates

- Stamps

- Overview of Tasmania

- Victoria

- Overview of Vic.

- Telegraph lines

- Telegraph offices

- Date stamps

- Forms

- Envelopes

- Rates

- Stamps

- Ephemera

- Western Australia

- Overview of WA

- Telegraph lines

- Telegraph Offices

- Date stamps

- Forms

- Envelopes

- Rates

- Stamps

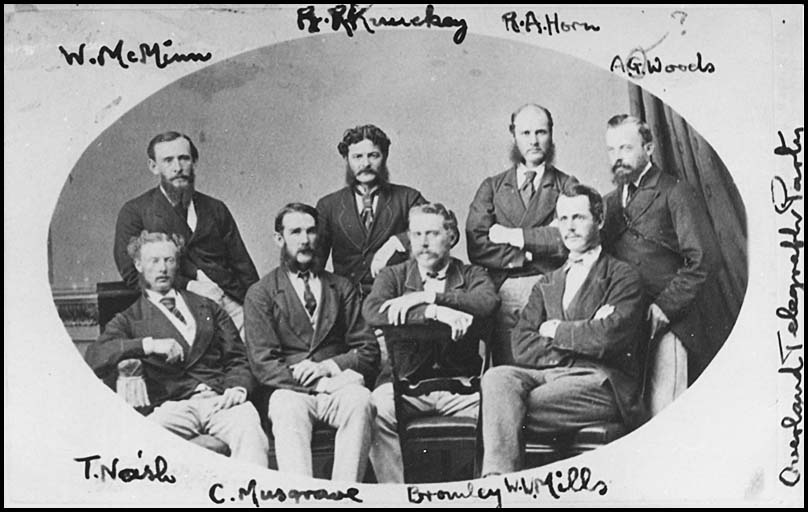

The main personnel.

There were of course many people involved in the construction of the Overland Telegraph Line. Many of those are long-since forgotten.

| In addition to Todd, the main planning and construction team consisted of some of those shown below. Most of these pioneers are referenced in the various pages - especially in the Line Construction section (see section 9). |

|

Many men died from such causes as attacks by the indigenous people concerned about their land, from starvation and dehydration and from becoming disoriented in the outback. Many women also died. They would be generally living in one of the stations or camps. Probably the most common cause of death amongst the women was childbirth.

Some stories are recorded. Others are not as it was regarded as part of the job. Historians have never really been interested in the OLT despite its importance. For example, there is no known date as to when the line ceased to operate.

A correspondent of the S. A. Register, one of the party which nearly succumbed to thirst, gives life-like particulars of the disaster from which the following account is taken:

An advance party of three operators — C. W. Kraegen, J. F. Mullen, and R. C. Watson — was dispatched from Charlotte Waters on the 8th December to the new station posts in the desert, with written directions as to the watercourses they would find. In the evening, after a hot and exhausting day's travel, they came, says the writer, to a tree in a creek on which was read in letters punctured in tin and affixed there, the announcement that water was to be had at the junction of that creek and the Hugh, about a mile from that spot; the next water by the road ten miles or what we took to be such.

Off we sped down the creek. What to us was a mile of hot sand and pebbles now? We would have water in a few minutes and all would be well. We got to the place, looked at the hole, found it dry, dry; went down the Hugh in the hot sand and blazing sun, but gave that up and returned. We dug with hands, tomahawks, knives — we had no shovel - but still no water could be got, and the terrible disappointment made all now feel the want much more than would have been the case but for being assured by the punctured tin announcement that water was to he had thereabout ; besides the efforts in the scorching, white sand, walking in it to a depth of 6 inches, digging as far as our arms would reach, perspiring and choking, had thoroughly exhausted two of us to such an extent that we had to lie down and rest.

Then the question arose, "what are we to do?" After much debate, it was determined to follow up the channel of the Hugh, which took a course a little west of that followed by the road, and try for water at any likely spot. The proposal was made that as the pack-horse was in need of a spell, the saddle-horse that had succumbed before could now hardly travel, two of us were really knocked up, and as the water could not surely be over five or six miles off at furthest, the third man should take his own and the other comparatively fresh saddle-horse and with three water-bags proceed at his best speed. The proposition was jumped at.

Away he went, promising to be back soon and we meantime felt assured that the rest would serve the two tired horses that remained and enable them to go on after all had a drink. We waited, thirsted, and still waited through many hours of a very close, warm night, but still no water came and, as patience had run out when the moon rose, we packed up, and leading the horses started on foot after the messenger. It would be impossible to tell all the speculations made and discussed to account for his non-return. He had abandoned us! He had lost his horses! He had lost his way! But, horror of horrors, he had not found water! These and many other surmises arose, and none had any comfort in them for us who were now almost speechless and helpless for want of a drink.

We made little progress; the horses travelled slowly, and we had often to lie down, put our nostrils close to the ground, and thereby obtain a breath of comparatively cool air — a thing we could not get whilst walking. We wearied ourselves going to and fro, and although travelling much, did not go far, and so Saturday passed away. On Sunday we could hardly stir. My companion says I talked an awful lot of "bosh". I am sure he did — "gabbled" is the word — unintelligibly, and laughed occasionally, but somehow we managed to try again for water in the creek. It must be there — and so at it we went again on Sunday morning, wearing finger nails off and drawing blood from the fingers, until our want of success left but one resource — one horse might be shot and its blood would help us to make an effort to get on. We shot a horse — the weakest — and having got what we desired from that source, again sought the road and rested. We had a good supply of liquid now — a quart potful each — and might rest a little before starting and we did. How hot it was! The sun poured down upon us and I really thought we should never get over the plain; but we did. We sat and suffered. The poor horse crawled, and doubtless also suffered. He seemed to go at the rate of half a mile an hour.

On we crawled, until on rising a bank we saw the bed of the Hugh once more. The horse pricked up his ears, mended his pace, reached the steep rocky bank, and of a sudden (thank the Lord!) we saw water — a small pool 18 inches by 30 inches, and only a foot deep, but water. Down the steep hill we went, got off the horse's back somehow and simultaneously man and beast plunged into the blessed liquid to satisfy an appalling thirst that had lasted from 8 o'clock on Friday morning, 8th December, until abont 2 p.m. on the Sunday following.

We rested the balance of that day, swigging water like a couple of dissipated fishes. On Monday, the 11th, we determined that as we could not go forward we would go back and meet the waggons. We led our horse and walked all the way. At the creek, we found that we had read sixteen for ten miles. We arrived at the Alice after walking through sixteen miles of sand, just in time to see some of the other party arriving from the opposite direction. They had found our pack-horse, but had heard nothing of our companion.

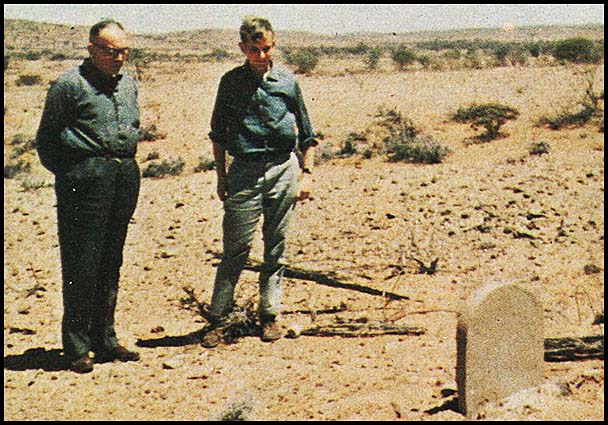

Finding Mr. Kraegen's Body.

One of the search party which was organised came on it at an angle-post about three miles from our camp and brought in his belt, found lying at his feet, and on which was his revolver, loaded all round, cartouche box and pouch. He left no scrap of writing, had no mark's about him; lay on his stomach, resting his head on the left arm, and holding his hat as if shielding his head from the morning Sun. His head was to the east, his face to the south, and not the faintest mark of a struggle appeared. He had evidently lain down exhausted, and quietly died for want of water nine or ten days before we saw him.

A grave was dug as near the spot as the stony nature of the ground permitted; and he was wrapped in a blanket and interred. Mr. Boucaut read the Church of England burial service over the remains, and caused a rough fence to be erected around the grave, against which bushes were placed to protect our departed companion's last earthly resting place from the native dogs. An inscription, punctured in tin, to the following effect, was attached to a stout board and fixed in place of a headstone:

" In memory of C. W. Kraegen, aged 40, who perished here for want of water, about 12 | 12 | '71. Buried 20 | 12 | '71.

Financing

Four of the Colonies paid an annual levy to support the construction and maintenance of the first line and later of the duplicate cable between Port Darwin and Penang. The basis of the levy was the number of people in the Colony.

In 1881, the Government of South Australia objected to the way the levy was imposed on the grounds that aboriginals were not included by Western Australia but were by the other three participating Colonies. I addition, South Australia had more aboriginals that the other Colonies and this was deemed to be unfair. Hence the basis was adjusted and South Australia received a reasonable reduction. See 1882 Annual Report for Victoria p. 18.

Batteries

The batteries along the line were Meidnyer cells filled with solutions of copper sulphate and magnesium sulphate. The cells were made fro glass and were 25 cm tall and 15 cm in diameter. Each operated at 1.5 volts. The Overland Telegraph Line worked at 120 volts and so many cells were required. At Daly waters, for example, there were 350 cells and a section was renewed each week so that the replacement of all cells took four months.